The Sloss Furnace halted its operation and closed in 1971 as new regulations such as the 1970 U.S. Clean Air Act had forced many of the older and less-efficient smelting factories to shut down. This was compounded by the stiff competition from foreign companies such as Japanese plants which exported steel and iron to America at a substantially lower cost than those locally produced.

As such, older factories such as the Sloss Furnace were no longer profitable. After 90 years of operation, the blast furnace at Sloss Factory were silenced indefinitely in 1971.

A History of Sloss Furnace

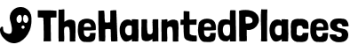

Construction of Sloss Furnace began in June 1881 at a fifty-acre site donated by Elyton Land Company. Founded by Colonel James Withers Sloss and designed by Harry Hargreaves, Sloss was Birimingham’s second blast furnace and the first to feature Thomas Whitwell’s state-of-the art stoves; the large-scale hot-air blast fire brick stove were much larger and more efficient than any similar system found in Southeastern region

Within a year since its completion in April 1882, Sloss Furnace had produced and sold over 24,000 tones of pig iron. Pig iron, also known as crude iron, is an intermediate product used in the production of steel.

In 1886, James W. Sloss sold Sloss Furnace company to a group of investors who went on to expand the company rapidy. By 1890, the company, renamed as Sloss-Sheffield Steel and Iron, was Birmingham District’s second largest producer of pig iron.

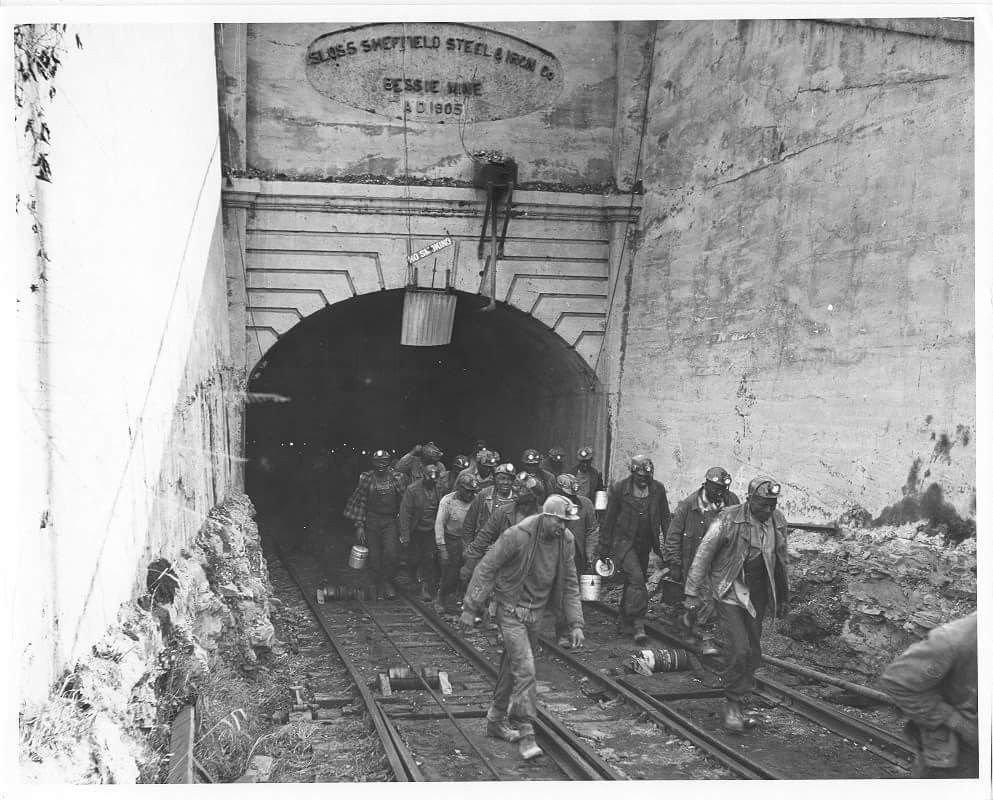

However, the company was known to exploit the convict-lease system which allowed them to employ prisoners—mostly African Americans—to work in the furnaces at little cost. There was a high degree of segregation, including a separate time clock and bathing house. More importantly, jobs were segregated. White workers dominated most managerial roles while black workers did laborious work such as the handling of molten iron and mining.

Over the decades, Sloss Furnace underwent several rounds of expansion including the acquisitions of other furnace and ore land. Existing factories were expanded and optimized to improve efficiency and output. This included the replacement of blast furnaces with larger and more efficient ones as well as the retrofitting of mechanical charging equipment to speed up production.

However, pollution became a serious issue in Birmingham due to the concentration of iron and steel factories in the state. On 31 December, 1970, President Richard Nixon signed the Clean Air Amendments of 1970, effectively forcing the closure of many old and inefficient blast furnaces in the country. In 1971, Sloss Furnace halted its operations and shut down, citing the Clean Air Act as the main reason for its closure.

In 1981, the site was designated as a National Historic Landmark.

Separately in September 1983, Sloss Furnace opened its gates to the public as U.S. first and only blast furnace site-turned museum. It is also the only 20th century blast furnace in the country being preserved as an historic industrial site, a true testament to Sloss Furnace contributions to the iron and steel industry.

Today, the site runs a host of activities ranging from art classes and weddings to educational exhibitions and food festivals. In 2022, Sloss Furnace museum will be hosting the 2022 World Hunger Games.

Deaths at the Furnace

Due to the nature of the industry, working conditions at Sloss Furnace were tough. Workers had to work with hot molten steel while enduring low visibility, hazardous gas, and temperatures of up to 120 degrees. As such, many fatal incidents have occurred at Sloss Furnace.

The first recorded death is said to have occurred right on the opening month of Sloss. Two worker, Aleck King and Bob May, reportedly fainted after inhaling toxic smoke and fell to their death into a furnace. In the same week, a worker named Samuel Cunningham committed suicide by diving into a furnace filled with hot molten steel.

Other forms of deaths reported in the site include getting crushed to death by gigantic wheel cogs and being scalded to death by bursts of hot steam.

The most infamous death in Sloss Furnace is perhaps James Robert Wormwood. Also known as “Slag” by those who work under him, Wormwood was an oppressive foreman in-charge of the graveyard shift. It is said that Wormwood would force his workers to work with minimal rest to speed up production in order to meet the quotas and impress the upper management. An estimated 47 workers died and many more injured during his reign.

One day, Wormwood was working at the top of Big Alice—the highest furnace at Sloss—when he slipped and fell into a pool of molten iron. While it is surmised that he had fainted and fell into the furnace after inhaling methane gas, many believed that it was the workers who conspired to kill Wormwood by pushing him into Big Alice. Nonethless, no workers were ever investigated for his death. Since Wormwood’s death, the company discontinued the graveyard shift.

Ghosts of Sloss Furnace

Since the opening of Sloss Furnace museum, visitors have reported strange activities and unexplainable occurrences. These include heavy footsteps, cold spots, loud voices, and dark figures. Many believe that these paranormal activities are the works of the spirits of those who have worked and met their fate in Sloss Furnace.

Some have also encountered a white, malevolent figure believed to be the ghost of James Wormwood. This apparition is said to be hostile towards visitors, with many reporting being pushed from the back and having faint scratches on their forearm.

The numerous hauntings at Sloss Furnace have attracted a slew of paranormal investigators to the site. Many, including Travel Channe’s Ghost Adventures from Travel Channel, Syfy’s Ghost Hunters, and Fox’s Scariest Places on Earth have reported or captured paranormal activities on the 18-acre attraction that many have lived and died.